In March and April of 2025, the U.S. stock market suffered one of the worst crashes of the 21st century. The reason? The administration of President Donald Trump imposed a series of tariffs that changed almost daily. Tariffs on Chinese goods, for instance, started at 74% and then skyrocketed to 145% in mere days.

As prices on household goods continue to rise, many Americans seek to counter their anxieties with knowledge. Many are now turning to the past to understand the present. Why have governments historically imposed tariffs? Are tariffs inherently destabilizing on a nation’s economy, or can they be beneficial?

For many in the U.S., the eternal city of Rome, which continues to have plenty for visitors to do today, has a long history that serves as an inspiration and model for many aspects of American life. As luck would have it, the Ancient Romans had tariffs, too. Understanding these tariffs in particular can help illuminate aspects of 2025’s economic problems that we can’t immediately see.

How did these differ from America’s 2025 tariffs? Is there anything that American policymakers can glean from Rome’s tariff example?

Related

All Money Today Stems From This 2,500-Year-Old Gold Coin

Ancient historians recorded legends about the invention of the first coins, and archaeologists have found some surprising evidence.

What Is A Tariff? Why Do Countries Use Them?

Tariffs are a taxation tool governments use to nudge their citizens into buying domestic goods

Seeing the destruction the current tariffs have done to the U.S. stock market, many are wondering why a country would employ tariffs. Others yet are wondering what a tariff even is. A tariff is a tax on imported products that the buyer of that product pays. In short, a tariff is a tax that makes things more expensive.

If they make things more expensive, are tariffs bad? Not necessarily! Tariffs are simply a way for governments to manipulate populations economically to further larger foreign or domestic interests.

For governments, tariffs can have many important uses. One use of tariffs might be when a government wants to encourage people to buy the same product from local businesses. For example, a country might put a tariff on foreign-made sweaters to encourage people to buy local sweaters instead.

Another use is when a government doesn’t want the population to buy products from a specific country. For example, if the country making the sweaters uses slave labor in production, the buying country might put tariffs on their products as a way of economically objecting.

Tariffs are also just a way that governments make money, plain and simple. If a government isn’t collecting enough taxes to make its fiscal operations feasible, it might decide to impose tariffs on popular products to generate revenue.

About Tariffs

|

What is a tariff? |

A tariff is a tax on imported products that the buyer of that product pays |

|

Why do countries use tariffs? |

To nudge their population into buying domestic products instead of foreign products |

|

What are some of the uses of tariffs? |

To generate income for the government, to protest against the actions of foreign governments, to encourage the purchase of domestic goods |

What Luxury Goods Did Ancient Rome Import?

The Romans imported at least $400 million USD worth of silk, spices, and incense every year

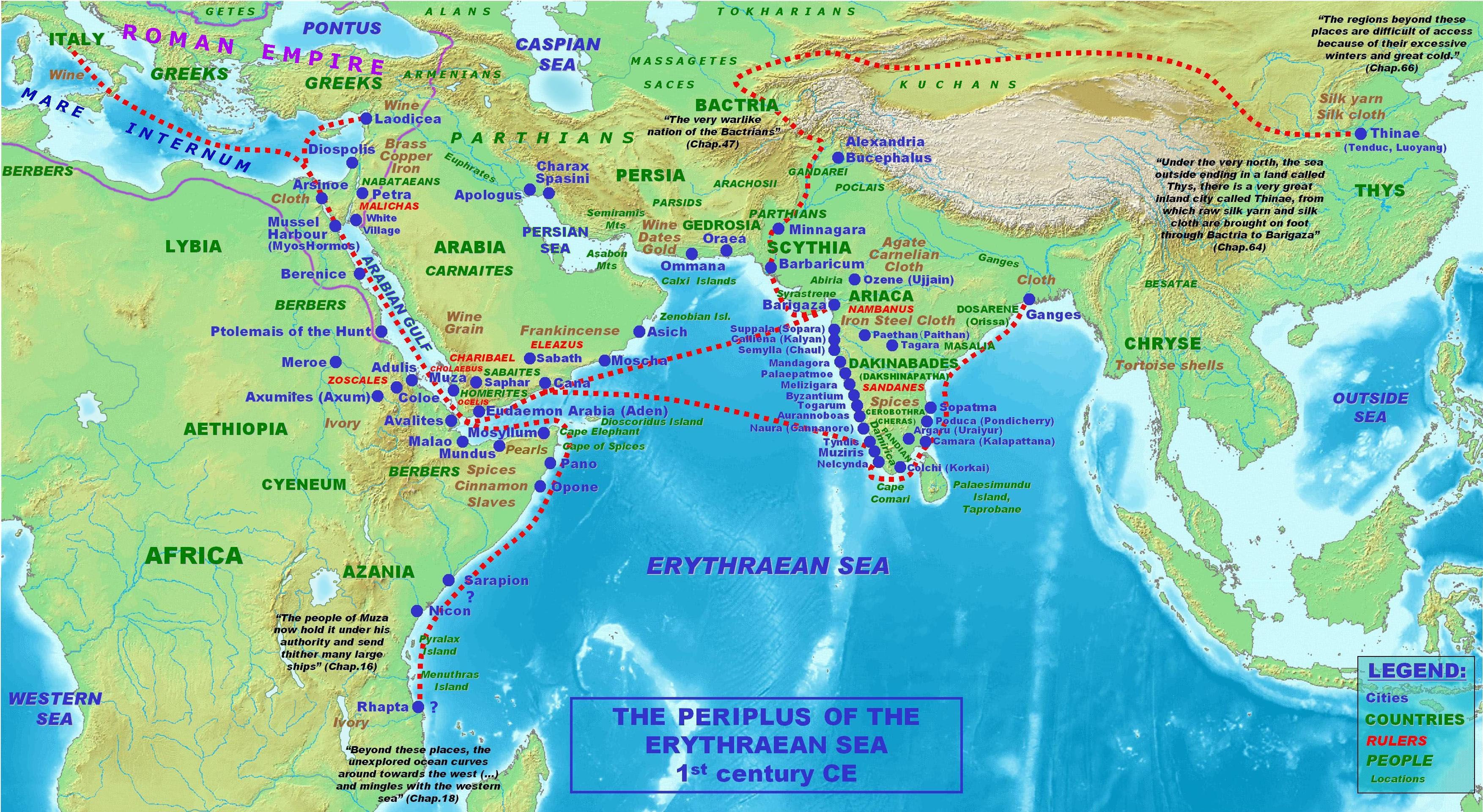

Map of the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea

Before discussing why Rome imposed tariffs on certain goods, we have to discuss what the Romans were importing. While the Romans imported goods from all over the known world, the most prestigious goods came from the east, specifically from Arabia, India, China, and even Southeast Asia. The Roman author, Pliny the Elder (who died during the destructive eruption of Mount Vesuvius), writes in his Natural History 12.41:

At the very lowest computation, India, the Seres, and the Arabian Peninsula, withdraw from our empire one hundred million sesterces every year—so dearly do we pay for our luxury and our women.

An analysis of Roman treasures that have sold for a fortune shows that IIS 100 million sesterces would be worth around $400 million USD…and Pliny says that’s a low estimate! Historian Peter Edwell suggests that this number was actually far higher than what Pliny suggests.

This is due to evidence such as the 2nd century CE Muziris Papyrus, which records a single Alexandrian merchant returning from Muziris (a city in India) with cargo worth IIS 9 million (or ~$36 million today). If one single merchant’s ship from one single trip contained that many luxury goods, it’s safe to say that Pliny was underestimating severely.

What were the Romans spending so much money on? Many of these goods are ones that we today still love. Silk fabric made from Chinese silkworms, precious pearls pulled up from the Red Sea, delicious spices like black pepper, shining jewels, and fragrant incense important for religious rituals all dominated Roman luxury markets.

While some of these goods, like black pepper, could be enjoyed by a wide array of the population (latrine analyses from Pompeii, such as those done in Cardo V, suggest that lower-income people still ate black pepper), others, such as silk, were harder to come by. Silk was so rare that it had to be interwoven with another material (most often cotton) to keep down costs.

Some even believe that the Servilia pearl (a famous historical piece of jewelry mentioned in The Life of Julius Caesar 50.2, a section of Suetonius’ Ancient Roman gossip book The Lives of the Twelve Caesars) was imported and bought for IIS 6 million sesterces. Some sources have claimed it to be worth as high as $1.5 billion dollars in today’s money, but the actual value would have been closer to $24 million.

All of these goods would have been taken to the Roman Empire through either Silk Road land routes or by maritime routes through the Erythraean and Red Seas (as highlighted in the ~2nd century CE Periplus of the Erythraean Sea by an unknown author). This would have driven their costs up significantly.

About Roman Trade

|

What did Rome import? |

Silk, precious jewels, pearls, incense, spices like black pepper |

|

Where did they import these goods from? |

China, India, Arabia, Southeast Asia |

|

How much did Romans spend on these goods, according to Pliny the Elder? |

|

Related

A new, groundbreaking study reveals a story of fraud, slavery, taxes, government, conspiracy, debt blackmail, and rebellion.

Why Were Roman Elite Men So Perturbed About Foreign Goods?

Rome’s elite felt that the import of spices, silks, and other luxury items weakened the Roman masculine virtue of virtus

In today’s U.S. political discourse, Americans decry foreign goods for a number of reasons. Some people believe that importing reduces American jobs and hope that the current tariffs will bring those jobs back. Others believe that importing more physical goods than a country is exporting is a bad thing in and of itself (the U.S. is the largest importer of goods in the world while simultaneously being the second-largest exporter). A small percentage of Americans feel slighted by the world and want revenge on international markets for “taking advantage of the United States.”

For Ancient Romans, international relations and the reduction of domestic jobs due to international labor weren’t really a cause for concern (the real threat to Roman domestic jobs wasn’t foreign markets, but instead was the growing use of slave labor on large plantation farms and in industry).

Although looking at the large number of imports might make some anxious, don’t let these numbers fool you. Rome was still exporting plenty of stuff. Roman glassware has been found in Han Dynasty Chinese tombs, and Roman coins have been found as far away as Japan. Metal objects, wine, cloth, coral jewelry, and slaves were all exported from the Roman Empire to East Asia according to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea (paragraph 49).

So what did concern Roman elites about imported goods? Turns out, it had little to do with economics, and far more to do with social status.

What Roman elites complained about wasn’t foreign trade, it was instead a perceived crisis of Roman masculinity. In the earlier quote from Pliny the Elder, hints of gender-frustration are immediately apparent. “So dearly do we pay for our luxury and our women,” he bemoans.

Members of Rome’s elite felt that enjoying luxury whittled away Roman manhood, which was founded upon austerity, paternalism, military strength, a rigid household structure, the Romans’ strict moral code called the mos maiorum, and, sadly often, cruelty.

This is not to be confused with the “gender war” rhetoric of today. One thing about the Ancient Romans that history books don’t always share is that for the Romans, maleness did not mean masculinity. One could be a “male” without being a “man.” Only male Roman citizens of free birth could be described by the Latin word vir (free citizen man); non-Roman men, slaves, and freedmen would have been called homo (male human), not vir (plus, male slaves were often called puer, meaning boy, a further diminution).

Wealth, social status, and military service greatly bolstered a free Roman man’s virtus (masculinity). By this definition, no Roman would ever consider any modern “male” to be a “man” because nobody alive today is an Ancient Roman citizen.

Roman Tariffs On Goods Imported From East Asia

The Romans put 25% tariffs on imported goods from China, India, Arabia, and Southeast Asia as a means to generate income for their government

Palmyra Tariff

In order to fiscally benefit from the countless goods flowing into the Empire, the Romans imposed passive tariffs on these imports. For goods being imported into the Empire from maritime routes, tariffs were set at 25%. This tariff, called the tetarte, was placed on the goods that were brought through Egypt and Arabia’s Red Sea ports.

Land-based tariffs didn’t have such an easy percentage assigned to them. Instead, an ancient inscription from 137 CE Palmyra (Syria), aptly called the Palmyra Tariff, details the appropriate amount of denarii to be paid per import. Goods subject to tariffs included purple dye, animals, ointments, olive oil, salted fish, animal fat, and even prostitutes and slaves.

These tariffs seem to be intended for governmental fiscal acquisition rather than punishing international markets. Most of the luxury goods that the Romans were importing from foreign markets were completely unavailable in the Mediterranean region; for example, silkworms were closely guarded in Ancient China and black pepper couldn’t be grown in the Mediterranean region during premodern periods.

Since these luxuries could only come into the Empire through foreign trade, they provided the Roman government with a stable source of tax revenue. People couldn’t turn to domestic markets for the same products since those domestic markets didn’t exist. They had to rely on foreign products, making the scheme a highly profitable one for the Roman government.

If Pliny the Elder was correct with his estimation of IIS 100 million sesterces being spent on imported goods from East Asia per year, this would mean that the Roman government would’ve collected IIS 25 million sesterces per year. Potentially, this number could have been even bigger, since Pliny’s estimate was low.

Ancient Roman Tariffs

|

What percent tariffs did the Roman government impose? |

25% on goods imported from East Asia through Red Sea ports |

|

What kind of goods were subject to tariffs coming via land? |

purple dye, animals, ointments, olive oil, salted fish, animal fat, and even prostitutes and slaves, according to the Palmyra Tariff |

|

How much revenue could the Roman government have generated due to these tariffs? |

|

Related

An Ancient Garden Was Just Uncovered In Rome

A Roman-era garden that belonged to one of Rome’s most infamous emperors was discovered by a construction team.

What Can The U.S. Learn From Roman Tariffs And Broader Economics?

Ancient Rome’s economic situation was very different from that in 2025 America, but there are still things Americans can learn from Rome’s tariffs

After learning how much money the Roman government drew in from tariffs, it can be tempting to project those figures onto the U.S. If tariffs were successful for the Roman government, why aren’t tariffs having success in 2025 America? There are a number of reasons why.

Firstly, the goods that were subject to tariffs were expected to be expensive already, and were non-essentials. People expected to pay these high amounts for certain goods. The Roman people knew that they had to rely on foreign markets for these goods and understood the lengths to which merchants had to go to get them; these ancient symbols of opulence, such as the one found in Nero’s gold house, were understood to be expensive.

For example, Pliny notes that Romans would pay exorbitant prices for black pepper. He writes in Natural History 12.14 that…

Both pepper and ginger grow wild in their respective countries, and yet here we buy them by weight—just as if they were so much gold or silver.

These tariffs worked, in part, because people were willing to pay them, and were already levied on goods that people expected to be expensive.

Secondly, the goods that were being imported benefited a portion of Rome’s economy and everyday people despite being expensive due to tariffs.

How? The reason is that the goods imported were often imported in their raw form. For example, silk was imported as fiber, and was transformed into cloth within Rome’s boundaries. Black pepper was likewise imported in bulk and then used by local restaurants.

These goods weren’t just nice, shiny things for rich Romans to buy; they also boosted local markets, too, and encouraged labor specialization. Plus, they didn’t directly compete with the goods strictly necessary for survival that were locally produced. So, while these goods were subject to tariffs, they nevertheless bolstered the Roman economy.

Thirdly, the reason tariffs worked for Rome, but aren’t working for the U.S., is because of the nature of their respective domestic markets. In the U.S., most everyday goods are produced in other countries. From the foods we eat to the clothes Americans wear to the technological devices we love, many of our household items are produced really far away from where they live.

Although Rome did have extensive trade between provinces, local economies were still often robust. Thus, the goods that were subject to tariffs were only a few specialized objects, not foundational goods and necessities. While Rome’s import tariffs on goods coming from the east were steep, they weren’t destabilizing to Rome’s domestic economy.

Rome’s domestic markets did have massive problems, though, with an over-reliance on slave labor being one of the biggest (slave labor created a huge wealth gap between Rome’s richest elite and their everyday people while also destroying jobs once held by free Roman citizens).

Finally, although these tariffs were beneficial for the Roman government, they weren’t enough to solve other economic problems that the Romans were having. Starting with Emperor Nero in 64 CE, Rome was increasingly faced with huge inflation problems.

A large reason for this was because of the debasement of the Roman currency. Silver coins, which were originally made with silver mined in Hispania, slowly became mixed with other metals to cut costs. This, however, had the unfortunate side effect of making those coins worth less than they had been before.

No tariffs or price edicts were enough to fix that underlying issue. A key lesson that the U.S. can learn about tariffs from Ancient Rome is that they can be a band-aid over a gaping economic wound, but aren’t enough to save a declining economy in the long run.

Ultimately, while the U.S.’ situation is immensely different from Rome’s, history can still be a teacher, and can point us towards wise economic policies.